Glacier San Quintin • Rio Acodado • Glacier HPN1 • Bahia Kelly • Laguna San Rafael • Isthmo Ofqui • Rio Negro • Rio San Tadeo • Fiordo Expedicion • Playa San Quintin • Punta Cuchilla • Punta Blanca • Rio Andres • Glacier Benito • Campo Hielo Norte • Rio Benito • Glacier HPN2 • Fiordo Benito • Glacier San Rafael • Rio HPN1 • Rio Blanco

Expedition Explorers II - PATAGONIA, CHILE, March 2009

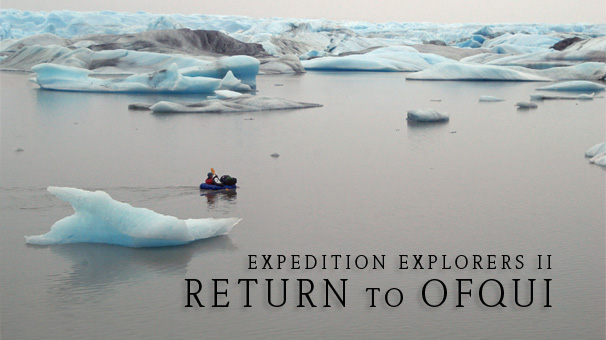

After our amazing experience packrafting in the region of the Northern Patagonian Ice Field in March of 2008, we decided we must come back to this region for more … more glaciers, more trekking, more paddling, more Patagonia. Expedition Explorers II: Return to Ofqui was in some ways a continuation of last year's adventures, when we packrafted from Valle Exploradores to Laguna San Rafael and back through the glacier valleys of Gualas and Reicher. However, it was also a completely new and different adventure altogether.

Expedition Explorers II was Antofaya's biggest adventure yet with first descents of glacial run-off rivers, visits to five very remote glaciers, some visited only by a handful of people and two that may never have been visited by anyone and are yet unnamed. We trekked across 30km (19 miles) of one of the most pristine and isolated beaches the mind could imagine and fought our way through thick brush and Patagonian jungle. We camped in front of glaciers, on the banks of rivers, in the middle of marshlands and on the edges of forests on whatever small piece of land offered to support our tiny, but rugged tent. We got strong, we got skinny and, some days, we got wet. But even in the rain, Patagonia reveals tantalizing hints of her charms shrouded in mysterious fogs and romantic mists. And on sunny days she stops your heart with stunning views, beautiful light, and wide open valleys that invite exploration. Rain or shine, Patagonia impresses, but she makes you work for your rewards. We like this about her.

|

|

|

|

|

After five tough weeks in Patagonia we remain enchanted by her challenge as well as her beauty. We are grateful and proud of what we have done there and hope to return again soon for another adventure. Over the past two years we have had the rare opportunity to visit these extremely remote corners of the earth, many which have likely never been visited before due to conditions and terrain.

It is not so important in terms of ego that we may be the first visitors to some of these far-flung places, but that it is actually possible for a couple of independent adventurers to find a corner of the world where perhaps no one else has been, where animals are unafraid, where the water is clean and clear. At a time when the environmental prognosis of our planet has been perpetually bleek, spending five weeks in totally unspoiled nature allows hope to soar anew. It also inspires me to imagine those places already spoiled by human needs and abilities and what they must have been like before their conquering. Imagine the beauty of the island of Manhattan for example, a forested isle bordered by two great rivers and the vast ocean—it must have been lovely.

For at least five weeks of our life, we were at the mercy of nature rather than the other way around and it was an oddly reassuring sensation to experience this more natural order. Even while this experience made us aware of our fragility and insignificance, it also reminded us that, stripped of all of the devices and social structures most of us are used to relying on, we can still take care of ourselves—we must take care of ourselves! This realization is one of an exhilarating, even intimidating, freedom. Of course we return to lives less intense, where we don't have to think so hard about our survival, where, in many ways, we are encouraged not to take care of ourselves. But the glaciers, the jungle, the marshes, the rivers, the rains, and the winds of Patagonia have taught us otherwise and we will remember.

|

|

|

|

|

Like the first Expedition Explorers, our adventures in Feb/Mar 2009 took place on the western side of the Northern Patagonian Ice Field, which has 28 exit glaciers. On this side of the ice field, only three of the glaciers are accessible by road or waterway. However, with a packraft 'accessible' becomes a relative term. During Expedition Explorers I, we visited remote Gualas and Reicher glaciers, two of the 'inaccessible' glaciers on the Northern Ice Field. It was our goal for Expedition Explorers II to visit San Quintin, Benito, and two of the unnamed glaciers south of Benito, officially called HPN1 and HPN2, all of which can be reached only by extraordinary means—with a packraft for example.

Laguna San Rafael and Ventisquero San Rafael (San Rafael Lake and Glacier)

We began Expedition Explorers II at Laguna San Rafael. This year, rather than paddling there in our packrafts we sailed to the laguna aboard a boat. A delegation from the boat left us off on the eastern side of the laguna. From there we needed to paddle about 15 kilometers (9 miles) around the perimeter of the fjord to reach the mouth of a small stream and the beginning of an ancient footpath on Istmo Ofqui that leads toward Rio Negro (Black River).

Istmo Ofqui (Ofqui Isthmus)

Istmo Ofqui is a strip of land that connects mainland Chile with the Taitao Peninsula to the west. It is a land barrier between the Laguna San Rafael and the Golfo de Penas (which translates as Gulf of Distress). The isthmus is largely marshland, crisscrossed by a network of rivers flowing southwest toward the gulf. The trail crossing the isthmus from Laguna San Rafael to the rivers leading south was long ago used by native Kawésgar indians. In the late 1800s and early 1900s plans for opening up a navigable channel at the site of the trail were discussed and initiated, but eventually abandoned. There are some old pictures showing the worker's cabins and men leaning on shovels in front of a wide hole in the earth. But now, the only sign of any human effort in this quiet place are a few planks of wood. The path from Laguna San Rafael to Rio Negro is easy to follow, but hard to trek because much of it is flooded and filled with deep, slippery mud that is easy for a trekker with a heavy load to get stuck in.

Rio Negro, Rio San Tadeo, and Fiordo Expedicion (Black River, San Tadeo River, Expedition Fjord)

The old trail ends where the land opens up into wide marshlands crossed with channels of black water that feed into the Rio Negro, and eventually the Rio San Tadeo. The Rio Negro's current is almost undetectable and, at times, paddling on the still black water feels like moving through a liquid mirror and it's hard not to feel a bit dizzy as your paddle penetrates the sky over and over again. We paddled on the Rio Negro and Rio San Tadeo for about 20 kilometers (12 miles) up to where the Rio San Tadeo empties into Fiordo Expedicion and meets Playa San Quintin.

|

|

|

|

Playa San Quintin (San Quintin Beach)

Playa San Quintin is a jaw-droppingly beautiful place and we felt extremely lucky to be there. Imagine: 30km (19 miles) of clean, perfect, virgin beach - no people, no trash. To the north there is a view of Glacier San Quintin, a blue and white monster across a huge field of marshes. To the south the green waves of the Pacific crashing furiously against the shore crank up the drama of the landscape. Punta Cuchillo, near the southeastern end of the beach looks at first glimpse like a tropical island paradise except with Patagonian rainforest under thick gray clouds instead of palm trees under blue skies. Walking the long 30-kilometer (19 miles) stretch of beach with our overweighted backpacks took us a couple of days. About mid-way and 3 kilometers (1.9 miles) from the end of the beach we had two river crossings that each required a change of modes from trekking to paddling and back to trekking, which was easy with our boats, but still ate up a lot of time.

Bahia Kelly and Rio Andres (Kelly Bay and Andres River)

We had to wait a day at Punta Blanca—at the eastern end of Playa San Quintin—for good weather to make the short, 2-km (1.2 miles) open water crossing of Bahia Kelly from Punta Blanca to the mouth of the Rio Andres. Once the weather cleared up a little and the wind died down, the crossing itself was not so difficult. We even managed to paddle upstream a bit into the mouth of the Rio Andres before we emerged, changed modes, and began our trek into the Andres Valley toward Benito Glacier.

Ventisquero Benito (Benito Glacier)

Bushwalking along the Rio Andres was not easy but nothing compared to what was to come. Penetrating the thick forest to reach Benito Glacier was downright arduous. In this forest, your feet rarely touch solid ground, which lies somewhere underneath multi-level layers of moss clumps and rotten trees. With each step you can sink down a couple of inches or a couple of feet. When we finally reached the top of the moraine, we were treated to a lovely view of Benito Glacier and an odd, magnificently blue tower of ice, much taller than the rest of the white and gray icebergs around it or even the glacier wall itself. We camped on a peninsula jutting into the proglacial lake surrounding Benito with the view of the glacier and this stunning blue iceberg surrounding us and doubled in the lake's still reflection.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rio Benito (Benito River)

We had a nice descent down the Benito River. There was one challenging section through a forest of dead trees, where avoiding half-rotten stumps in the water was a bit tricky in the faster sections. However, this section of the river was visually very interesting with banks of low, warm mist hanging over the river and dark, full-sized tree trunks, stripped bare of branches by wind and water, rising at odd angles like spears. At the mouth of the river we had to tow our boats through shallow areas and over sandbars until it was deep enough to paddle.

Fiordo Benito (Benito Fjord)

We paddled 5km (3 miles) across Fiordo Benito in light wind and waves, hugging the western wall. Two sea lions came over to check us out, alerting us of their presence with a startling and funny snort of air and water. We paddled into the mouth of the Rio Acodado just before sunset. Since we arrived at low tide, we hit sand and mud long before decent camping grounds and had to tow and portage to a better site. Along the way we were treated to a beautiful sunset that set the mist over the water aglow with a rather surreal pink light. The moon was so bright we could easily see our shadows and did not need to use our headlamps.

Rio Acodado (Acodado River)

After a day of heavy rains, we had a clear blue sky for our hike up the valley of the Rio Acodado. The vertical slopes of the valley's green walls were laced with waterfalls from the rains. The terrain along the Rio Acodado was very good for trekking, mostly moss-covered boulder fields and ankle-high brush with scattered bits of thicker and taller bushes. We had to make two river crossings at the beginning of our trek up the valley. After a pleasant but full day of hiking we arrived at the shores of the river that, further to the north, flows out of glacier HPN1, excited to explore the unnamed glaciers.

Unnamed Glaciers HPN1 and HPN2

Our day exploring the unnamed glaciers was perhaps the most rewarding day of the expedition and partly because of what preceded it. After two stormy days of pouring rain, ferocious winds, and even thunder, which is extremely rare in this wet region, we finally woke up to blue skies. Giddy to feel the sunshine on our backs and antsy to stretch our legs after two days in the tent, we strapped on light packs and set out on a day hike to explore HPN1 glacier.

HPN1 is a beautiful, very photogenic glacier. We inflated our boats and spent some time contemplating this lovely glacier from various vantage points before paddling into the mouth of the river for one of the most enjoyable river descents of our expedition. We ended the day by paddling into HPN2's lake and visiting this second unnamed glacier. This glacier was very tidy, with few icebergs floating in front of it and a long, clean line.

|

|

|

|

|

The Return Trip

Our return route found us trekking and paddling in familiar, but sometimes, unrecognizable territory. In Patagonia the weather paints the landscape, it can create two very different places with the same geographical location. This became especially noticeable to us as we trekked upstream along rivers we had descended or floated down rivers we had hiked along on the way out. What may have been a big open valley with impressive sheer granite walls one way was on the way back an eerie, foggy corridor marked by a sparse forest of dead trees rising out of the river. In photos, you would never guess they were the same place, in person only with a shrug of disbelief.

Ventisquero San Quintin (Glacier San Quintin)

We retraced our footsteps all the way back to Playa San Quintin, but from there, we changed our course. We trekked back across the beach up to the mouth of the Rio Nevado, and then turned to hike upstream through the marshes toward Glacier San Quintin. After a slightly harrowing hike through soggy marshes and thick brush, we emerged at the foot of the enormous Ventisquero (glacier) San Quintin. We arrived at the shores of San Quintin's glacial lake on a foggy afternoon. We could not see the glacier itself, which was completely shrouded in thick grey mist, but we could feel its massive presence. San Quintin is the the biggest glacier on the Northern Ice Field and dwarfs the next largest.

Paddling in and among the maze of icebergs surrounding San Quintin was challenging but fun. Paddling a small inflatable boat around chunks of ice with sharp melted edges can be a bit nervewracking, but our packrafts are so easy to maneuver that slaloming in and around them was not as difficult as it sounds. And, as we know by now, our boats are tough—very tough. We even slid over the top of one partially underwater iceberg to cross an area particularly choked with ice. We paddled about 2/3 of the perimeter of San Quintin's proglacial lake. When we reached a finger of land separating the main body of San Quintin from its northern arm, we changed modes and began to trek across this land bridge toward the shores of Rio Blanco, the river running out of the northern arm. The weather began to change as well and we finally had a beautiful close-up view of San Quintin.

Rio Blanco (White River)

Today we made our distance record for this expedition, paddling about 26km (16 miles) in total! We descended the 20km-long (12.5 miles) Rio Blanco from its origins flowing out of San Quintin's northern arm to its confluence with the Rio San Tadeo. The crux of our Rio Blanco descent was a section where the river spread out into a wide and shallow maze of marshes, dead tree trunks and narrow channels. This section required both a lot of towing in soft sand and cold waters and keen navigation. When we reached the Rio Blanco's confluence with the Rio San Tadeo, we kept going, paddling 6 more kilometers up against a light current the Rios San Tadeo and Negro before reaching our camp for the evening. Today we watched the water beneath our boats transform from icy gray to coffee-colored to black and felt its temperature change underneath our boats as we moved farther away from the glacier and into the marshes.

|

|

|

|

|

Return to Ofqui

Paddling up the last part of the Rio Negro to the marshlands and the path back to Laguna San Rafael was nearly as easy as it had been paddling down the river. The current on this still black water is almost negligible. We were led part of the way by a graceful black-necked swan that we had seen on our way out as well.

We arrived back at Laguna San Rafael early in the afternoon. Somehow, this isolated laguna that to most who visit it, viewing it from the deck of a large ship, feels alien and untouchable, had become, to us, a familiar and reassuring place.

We had three days to meet our pickup on the other side of the laguna, which was 14km (8.7 miles) paddling straight across. It was enough time, but knowing Patagonia as we were getting to know her, we realized there was a small chance we would not make it if the weather was threatening. Wind and waves in this tidewater laguna can be serious business, something we learned on the first Expedition Explorers.

Crossing Laguna San Rafael

Indeed, a storm rocked the laguna and we spent a day and a night listening to the laguna tossing huge icebergs into each other and against the shore, unthinkable conditions for a packraft. The next day dawned rainy and a little windy, but much calmer than the day before. With just two more days to go before our pickup, we decided to brave the waves and go for it, or at least give it a go part way and see how we were doing. Though nothing like the storm waves of yesterday, the waves still rocked our little boats and made paddling extra difficult. For the first 7km (4.3 miles) we had the wind at our backs, but the remaining 6km (3.7 miles) to get to the opposite shore were straight into the wind and against the waves. It took every last bit of strength we had, but we ended our expedition with our biggest open water crossing ever at 14km (8.7 miles).

Back to Civilization … Well Sort of

When we made it to the other side of the laguna, where we would meet our pickup, we were greeted by a group of glaciologists who were gathering imaging data for research on the ice flow of Glacier San Rafael. They kindly adopted us, promptly fed us eggs, tea, bread, chocolate … PEANUT BUTTER and other unimaginable luxuries. In just a couple of days we were back in Puerto Montt reeling from the strangeness of once again being among crowds of people after five solitary weeks in the wilderness.

|

|

|

|

• Dates: February 23, 2009 to March 30, 2008—36 days

• Start and End Point: Laguna San Rafael, Northern Patagonian Ice Field, Aysen Region, Chile

• Furthest locations reached: HPN1 and HPN2 glaciers

• Participants: Jarek Wieczorek, Krakow, Poland and Rianna Riegelman, Denver, Colorado, USA

• Distance covered: 282 kilometers (175 miles) paddling 60%, trekking 40%

• Glaciers Visited: Benito, HPN1 (likely first visitors ever), HPN2 (likely first visitors ever), San Quintin, San Rafael

• Rivers Descended: Rio Acodado (possible first descent), Rio Andre, Rio Benito (possible first descent), Rio HPN1 (first descent), Rio Blanco, Rio Negro, Rio San Tadeo

• Open Water Crossings: Bahia Kelly (2km, 1.2 miles), Fiordo Benito (5km, 3.1 miles), Laguna San Rafael (14km, 8.7 miles—our longest open water crossing ever in our packrafts)

• Weight carried: 32kg (71lbs) and 35kg (77lbs) on first day of the the expedition

Flora and Fauna Sightings:

Animals:

• Marine Otter (Lontra Felina):

Called chungungo or gatito del mar (cat of the sea) by locals, Marine Otters are extremely rare and are listed by some countries as endangered animals.

• We have not been able to confirm the identity of a smaller animal we saw on both expeditions, but the most likely candidate is an American Mink (Mustela vison), an animal that was introduced to the area and one that has endangered native frog and bird species in various regions of southern Chile.

• Sea Lions

• Dolphins

• Variety of frogs and toads in the marshes near Rio Negro

Birds:

• Black-Necked Swans (cygnus melancoryphus)

• Cormorandts

• Herons

• Seagulls

• Green Parrots

• Finches

• Hummingbirds (Picaflor or Colibri in Spanish)

• Turkey Vulture (Cathartes aura, Jote in Spanish)

Plants:

• Nalca (Gunnera tinctoria)

Known in English as Chilean Rhubarb, this plant has edible stalks and its leafs can grow up to 2.5 meters (8 feet) in width. Because of their size, shape and strength, these leaves can make a great umbrella for hiding from Patagonian rains. They are traditionally used by locales of the island of Chiloe to cover curanto, a stew that is cooked with hot stones in the earth.

• Calafate (Berberis buxifolia)

Called Magellan Barberry in English, this is an evergreen bush with edible bluish black berries that are both eaten fresh and used for making preserves and pastries.

• Copihue (Lapageria rosea

Called Chilean Bellflower in English, this is Chile's national flower

• Huge variety of mosses and lichens

• Wild Sweet Peas

• Wild Strawberries

Human Sightings:

None

|

|

|

cellular: (in Chile) +56 9-8269-6562

website: www.antofaya.com

email: jarek@antofaya.com

Text by Rianna Riegelman

Photos by Jaroslaw Zygmunt Wieczorek and Rianna Riegelman

More photos from Expedition Explorers II - Return to Ofqui can be found on Jaroslaw's "What's Cooking?" web gallery at digitalitis.com.

Contact our guide to set up a custom itinerary in Chile or Argentina

About Antofaya | Overland and Trekking | Paragliding | Trip Galleries | Contact | Facebook ![]()

|

Official importer and distributor in Chile of Alpacka packrafts and AirCross performance paragliders |

|

Site designed by Rianna Riegelman, riegelmanbookworks.com

All text and images found on this site, unless otherwise indicated,

are the property of Antofaya Expeditions and Digitalitis.com

2010 © Copyright Antofaya Expeditions